I came into American Fiction somewhat cautious, but mostly optimistic. I love the whole cast, and I love a satire. The premise—a pretentious Black author pretends to be a thug in a The Producers-style bid to insult white publishers and Make A Point, only to become more successful than he’s ever been—was intriguing. And I tried to ignore the annoying questions a friend posed to me, like “didn’t they make this movie already?” and “does the target of this satire even make sense today?” I was determined.

My optimism died pretty quickly into the movie, as it made one bewildering choice after another. By the end, I was simply befuddled. What happened to the hilarious satire that came with such glowing reviews? What happened to the point?

I stayed befuddled, and grew increasingly angry, as American Fiction’s Oscar campaign picked up steam. That campaign ended this week in some gold for Cord Jefferson, who adapted the novel Erasure into this screenplay. And then, in front of the press pool, Jefferson had this to say:

“Hopefully the lesson here is there is an audience for things that are different. There is an appetite for things that are different and a story with Black characters that’s going to appeal to a lot of people…[Black films don’t] need to take place on a plantation, they don’t need to take place in the projects. It doesn’t need to have drug dealers in it and doesn’t need to have gang members in it. There’s an audience and market for depictions of Black life that are as broad and as deep as any other depictions of people’s lives.”

And I can’t keep my complaints to myself* anymore. We must leave this—analysis is too generous for what this is. Twitter theory, perhaps?—where it belongs. And to be honest, it really belongs in 2003.

*editor’s note: Marion has never kept her complaints to herself.

What was the last plantation movie that really dominated the American zeitgeist? No need to look it up—it was 12 Years A Slave. Which came out 11 years ago. That was also the last time someone won an Oscar for playing a slave. Since then, Black Panther rocked the superhero movie world, and Get Out supercharged the entire horror genre. Two of the most infamous Oscar moments of the decade since have had Black movies at the center of them: Moonlight winning Best Picture despite a confused septuagenarian’s best efforts; and The Slap happening right before Questlove won his Oscar for Documentary Feature*, and Will Smith won his Oscar for playing Richard Williams. Not a plantation narrative in sight. Since 12 Years a Slave, Viola Davis, Mahershala Ali, Regina King, Daniel Kaluuya, and Da’Vine Joy Randolph have also won acting Oscars, and none of them set foot on a plantation to do so. In Jefferson’s own field, the last Black person to win a Screenplay Oscar was Jordan Peele, in 2018, for Get Out. Notably, not a plantation movie. Pettily, an ORIGINAL screenplay, rather than an adaptation.

But let’s zoom out from the Oscars and include the subject of American Fiction’s plot. Jefferson’s understanding of the Black narratives that dominate the literary market is similarly outdated. Nobody is checking for hood narratives right now. Nobody has been for decades. Jeffrey Wright’s Monk is up here mad about Get Rich or Die Tryin’ of all things, like that movie didn’t come out in 2005 and didn’t make $46 million on a $40 million budget. That’s not your enemy, sir.

Your actual enemy is a highly credentialed West African/first- or second-generation West African-American, if we’re being for real. It’s Chimamanda, Yaa Gyasi, Tomi Adeyemi. It’s women exactly like me. Or, more to the point, exactly like Issa Rae, whose role in American Fiction could have been so illuminating, so full of genuine challenge, but was instead so disappointing.

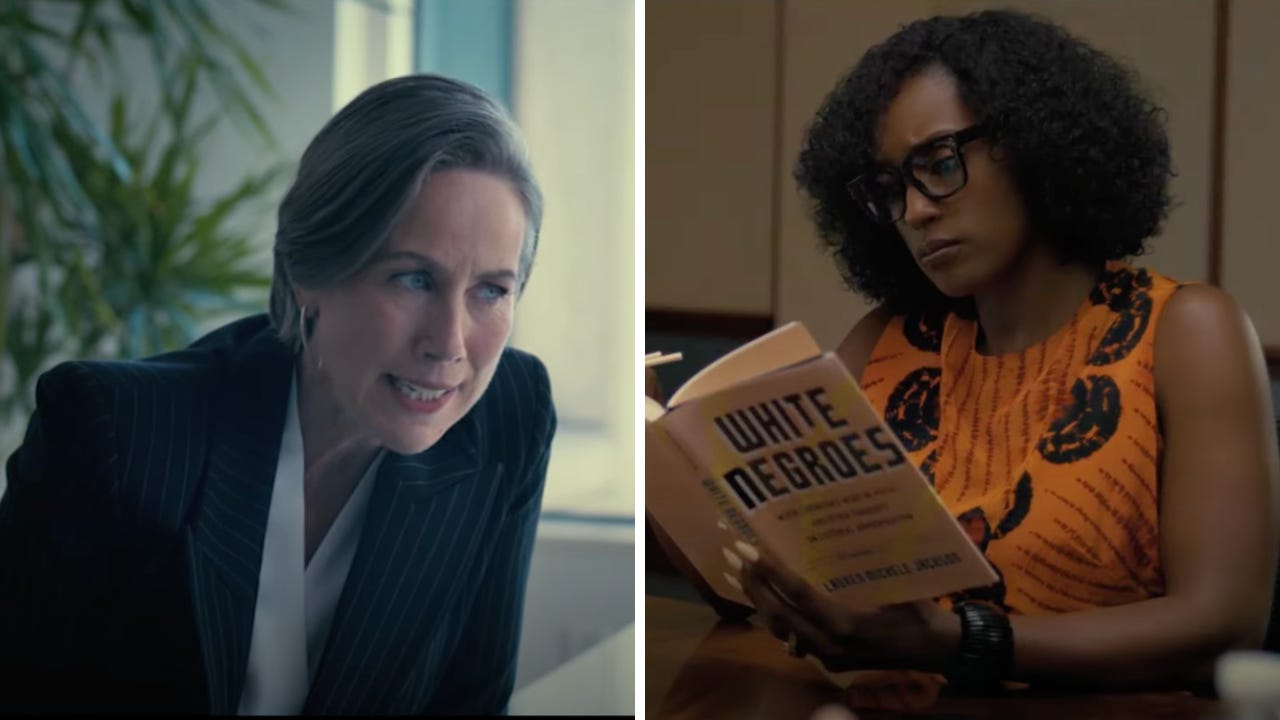

Rae’s character, Sintara Golden, is initially presented as everything Wright’s Monk hates. She’s a sellout who appropriates poor Black people’s stories and culture for clout, while pretending that her own success means success for “my people.” Once Monk actually meets her, though, she’s surprisingly thoughtful and principled, and seems to be the only person who sees through his book’s fakery. Then, in the film’s most flabbergasting scene, she defends her writing as being well researched and “what publishers want,” and accuses Monk of being the self-loathing snob. Which is true, but, sis. The call is also coming from inside the house.

I had been trying to keep utter despair over this movie at bay with the thought that perhaps it’s all a big meta joke. In adapting this satire, maybe Jefferson wrote the exact kind of movie he wants to satirize—something toothless, evasive, and directed at an audience of animate “in this house, we believe” signs. That would be kind of flamboyantly awesome, right? But I think that tiny, defiantly hopeful part of me is giving everyone too much credit here.

As an avid consumer of media that’s mostly about me and people like me, American Fiction should have challenged me specifically. But instead, it chose a target that can’t get upset because it doesn’t even exist anymore, and the man behind the screenplay promoted it by choosing a target that only exists in the minds of people who don’t consume any Black media. There is a lot to be said about which Black stories are in high demand and why. American Fiction doesn’t say any of it. And, based on how Cord Jefferson talks about any of this stuff, it’s easy to see why.